The indigent circumstances of his childhood meant his family could not afford outside studies, and thus the only education that he received was from his uncle, Sun Wanxia, the younger brother of his father. Sun met his father for the first time at the age of nine. At nineteen, he married Wang Caiwei. The couple lived with Wanxia's father, Wang Guangxie, and Sun Xingyan attended the Longchen Academy. Afterwards, because of the county level imperial exam, his fame as a poet started to spread in the Wujin district of Jiangsu. Sun Xingyan came to be considered one of the "Seven Sons of Pi Ling," a group of famed scholars from Pi Ling, an area now known as Changzhou. Out of the "Seven Sons," Sun is the youngest, as well as originally having come from the poorest economic background.

Sun's wife, Wang Caiwei passed away in the forty-first year of Qianlong's reign. His wife's death was a heavy blow to Sun, who "in grief, reckoning that a happily married couple is hard to come by, swears to never marry again". Following the passing of his wife, Sun, who had yet to take and pass the imperial exam, was hired as an assistant to Biyuan, a well-known official and scholar of the Qing Dynasty. Other noted Qing scholars who also worked for Biyuan at this point of time were Zhaoyi (Qing Dynasty historian, and one of the three great historians of the Qianlong era), Qian Daxin, and Jiang Hening. During this period, Sun gradually turned his focus from poetry to textual criticism, a branch of textual scholarship, philology and literary criticism that is concerned with the identification and removal of transcription error in texts.

In the fifty-second year of Qianlong's reign (1787), Sun was the second highest-ranked candidate (known as bangyan) to pass the imperial examination, and began editorial work at Hanlinyuan, or Imperial Hanlin Academy. While living in Beijing, Sun's home became a gathering place of repose and conversation for scholars and the literati, including Korean Goryeo envoy Chen Pu, who called to pay his respects to Sun at his residence. From the fifty-second to the sixtieth year of Qianlong's reign, Sun resided in Beijing for a total of eight years as a government official, with numberless interactions and correspondence with Beijing's literati scholars, and his close friends.

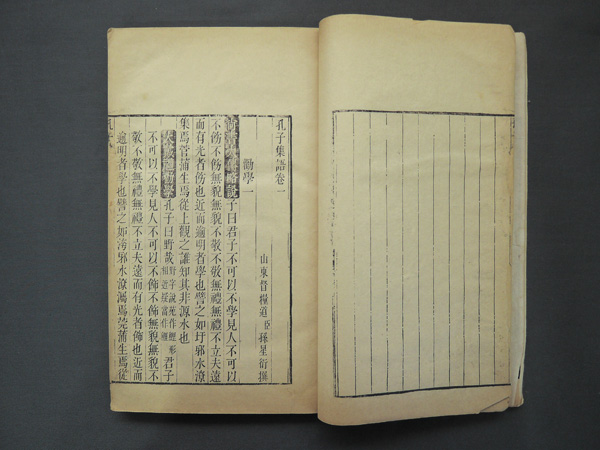

In the fifth month of the sixtieth year of Qianlong's reign (1795), Sun was appointed to a post at Shandong, away from the capital. In the third year of Jiaqing's reign (1798), he returned to Jinling for the mourning period after the death of his mother, staying there until the ninth year of Jiaqing's reign before returning to Shandong to become a supervisor of the food routes. In the period that he was in Shandong, Sun advanced his work of textual criticism of ancient texts greatly, including Dai Nan Ge Cong Shu and Ping Jin Guan Cong Shu, which are considered Sun's greatest contributions to the field of guji (ancient text) criticism. This work of textual criticism was a time-consuming but important process, which involved comparing all the available editions for transcription errors. This work required a firm understanding of not only Chinese history, but also etymology, which included philological knowledge (how changes in the form and meaning of the word can be traced), and semantic and phonetic changes.

In the seventh month of the sixteenth year of Emperor Jiaqing, he returned to his hometown due to illness. Despite his illness, he nevertheless continued his work on writing, and on proofreading and editing antiquarian books. In the twenty-third year of Jiaqing's rule (1818), Sun's chronic ill-health overtook him and he passed away.

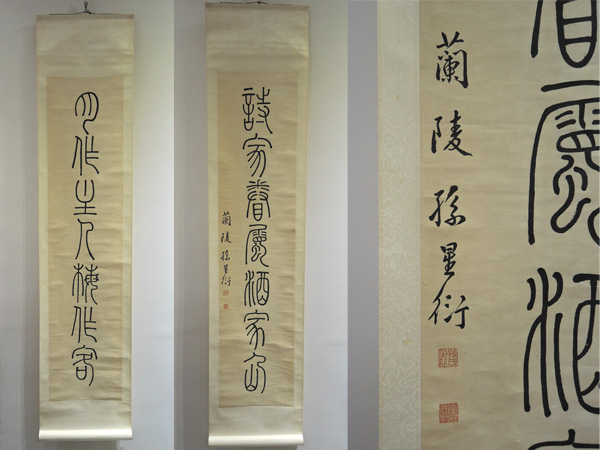

Before Sun Yingxan became an official, he was already widely-known for his poetic and literary accomplishments. He later turned his focus on textual criticism of antiquarian books. His editing efforts were of great caliber, leaving behind rich materials and literary works for later generations. Apart from this, Sun was also a talented calligrapher, especially in the style of the seal script.

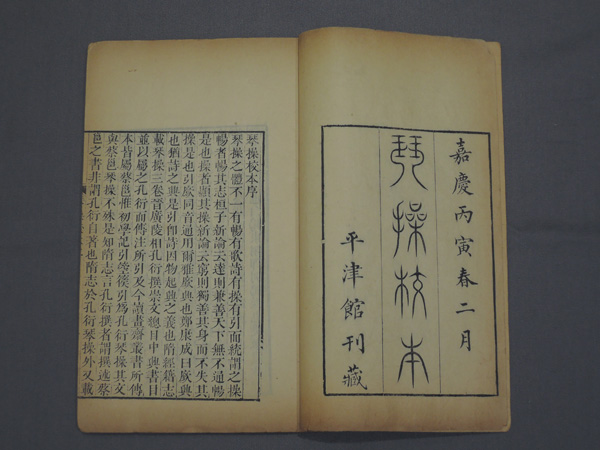

Dai Nan Ge Cong Shu and Ping Jin Guan Cong Shu are viewed as Sun Xingyan's most significant work in editing and textual criticism. In addition to the learning and skills that Sun himself brought into the work, other famed textual scholars such as Gu Qianli and Hong Yixuan, and renowned woodblock carver Liu Wen Kui and his brothers, who carved the woodblocks for the printing and publishing of the texts. It is no wonder that Sun felt considerable pride in his work on Ping Jin Guang Cong Shu, even going so far as to say that he would welcome open scrutinization of his work, confident that no mistakes would be found.

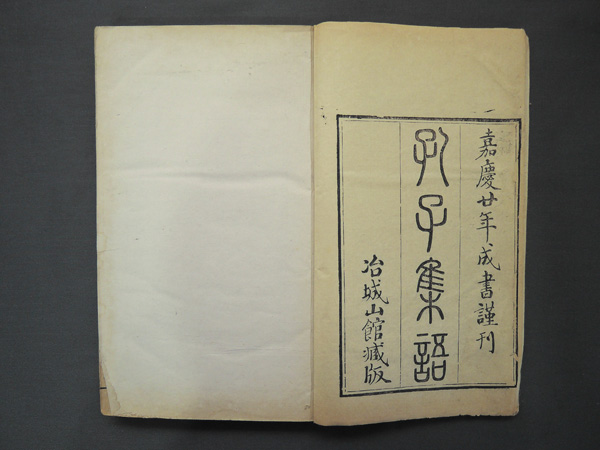

Dai Nan Ge Cong Shu was published in portions, beginning in the fiftieth year of Qianlong's reign, with its last portion being published in the fourteenth year (1809) of the reign of Jiaqing. This series of books was so named since Sun's place of residence when he was posted in Shandong Yanyi Caoji was to the south of Daishan. There are 23 types and 173 volumes.

Ping Jin Guan Cong Shu was named after the place of where he was stationed in Shandong as an official supervising the food distribution routes, a place which in the Han Dynastywas the fiefdam of Ping Jin. There are 43 types and 254 volumes.

Sun Xingyan's childhood was one of poor economic circumstances, thus buying books was a luxury he could not afford. It was only after he passed with brilliant results the imperial examination, and took up the post of a government official, that he came to have some level of wealth. At that point of time, he started collecting shan ben (a special categorization of old books that are considered reliable in accuracy), and came across the texts Sun Shi Ci Tang Shu Mu, Ping Jin Guan Jian Cang Ji, and Lian Shi Ju Cang Shu Ji.

His several libraries included "Sun Shi Ci Tang" (also called "Wu Song Yuan," "Lian Shi Ju," "Ye Cheng Shan Guan," " Shu Ting"), "Pin Jin Guan," "Wen Zi Tang," and "Yi Xie Yuan."

Sun's book collection tragically sustained great damage in the third year of Jiaqing's reign—while Sun had returned to Jinling due to his mother's passing, bringing with him a vast number of his books and scrolls. As Sun recounts the experience, "The Yellow River overflowed, boundless, gales blowing as the boat crossed Weishan Lake in Tengxian (county), boat almost capsizing…when the wind lulled, the boat anchored, but the boat in front sunk, drenching many books and paintings…more than half of his books lost by the time [he] reached Jinling." Perhaps what was even a greater loss than what this flooding incident caused was the neglect of his book collections after Sun's death. The Taiping Rebellion threw China into Turmoil in the 1850s, and Sun's library collection and his carved printing boards were for the most part destroyed in the ravages of the war. In the late Qing and early Republic period, quite a few book collectors, including Lu Xinyuan, Ding Bing, Qu Yong, Li Sheng Duo, Han Fenlou, were able to obtain items that belonged to Sun Xing Yan's shelves. On the "List of China's shanben ," there are more than 70 books that once belonged to Sun's library that are included.

2. Shanben (善本) are versions of ancient texts that are considered rare and least devoid of transcription errors.

|

| 《孔子集語》 |

|

| 《琴操》 |

Database of Ancient Chinese Texts series: